There were many things from the recent settlement of Fair Lending and Fair Housing Claims against BancorpSouth that didn’t surprised me (see United States of American and Consumer Financial Protection Bureau v. BancorpSouth Bank, Case No. 1:16cv118-GHD-DAS, U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Mississippi, Aberdeen Division). I was not surprised that BancorpSouth settled a Fair Lending investigation since it had been fairly well known that the bank was undergoing an investigation that had put on hold its regulatory applications for two planned bank acquisitions. I also was not surprised that a Mississippi bank was the subject of such an investigation since Federal regulators have long utilized Mississippi’s tortuous and inescapable past as a reason to plow its fertile ground and harvest a rich political yield in the form Fair Lending investigations. This regulatory tendency has existed at least a decade, going back to when the FDIC started sending Mississippi banks nasty letters about their HMDA data. There were three big points worth noting, though, some of which were concepts I already knew but had reinforced by the settlement. Others, however, were eye-opening revelations. Below is a description of each.

- HMDA Data Matters

I have never represented BancorpSouth on this or any other matter so I don’t have any knowledge of how this investigation began or what exactly triggered it. However, by reading through the lines in the complaint, there are too many references to “regression analysis,” “statistically significant” rate differentials, and the Memphis MSA to not think that it may have begun as a review of the bank’s HMDA data from Memphis. That is just a guess, but based on prior experience, it seems to be a good one. The way these things typically play out, the Feds, after sticking their statistics geeks in the corner with a bank’s HMDA data, find that there are statically significant differentials as to interest rates charged or denial rates for minority borrowers relative to non-minority borrowers.

Their questions start out benign at first, asking whether these differentials can be explained by business non-discriminatory reasons. What they are looking for is for you to provide them a rate sheet, loan policy, or some other objective measure that shows why the mortgage borrowers were charged a certain rate on a certain loan or why a minority borrower was denied credit. If they select a sample of loans and find that the rates charged followed closely a standard rate sheet used to price mortgage loans, or if denials of minority applications were the result of the applicant clearly not meeting objective credit standards stipulated in their loan policies, and those factors were carefully documented in the file as the reason for the decision made by the loan officer, the regulators will conclude (hopefully) that the “statistically significant” differences were caused by other non-discriminatory factors and move on to their next prey, I mean bank. However, if they take a sample to test, and in the process cannot find any objective reason for why minority borrowers would be treated differently, the bank that is the object of the investigation had better hold on; it is going to be a bumpy ride! This leads me to my second point . . .

- Underwriting Discretion is the Fair Lending Death Nail

I am the son of a community banker. Like all of us, I remember asking my dad one time when I was small why he decided to pick his career. His dad became a banker later in life, and both of my dad’s older brothers are bankers, so his choice was not a novel one. Family influence, though, was not the reason he gave. Instead, my dad believed that, as a community banker, he had the opportunity to help people meet the needs of their businesses and families. Of course, one of the greatest tools a community banker has in his or her toolbox to pursue this divine calling is good common sense to exercise reasonable discretion when warranted. Not only does it assist the community banker in pulling that customer out of a tough financial place in life, it also allows the community banker to compete with larger, less flexible institutions that have a tremendous advantage when it comes to economies of scale, especially in today’s compliance environment.

That tool now, though, has become the regulator’s number one enemy. When it comes to Fair Lending, discretion is a four letter word, especially as to HMDA reportable loans. If your bank’s LAR reveals that rates paid by minority borrowers or women are slightly higher on average than the control group, and they discover that your loan officers have the discretion to assign to borrowers whatever rates they, in their professional opinion, deem appropriate, your bank is presumed to be guilty of discriminating against minority borrowers until you somehow prove yourself innocent. This all but forces banks to standardize their pricing and credit decisions, turning consumer credit into a commodity and erasing any competitive advantage community banks may have on such loans over their larger brethren that see the borrower as another number. Unfortunately, what regulators don’t realize is that the one who really suffers is the borrower, black or white, who just needs a break to get over that next financial hurdle. After all, you don’t receive any compassion from a loan policy or a rate sheet.

- The CFPB is Taking No Prisoners

I’m sure no one was shocked that the CFPB would aggressively pursue fair lending enforcement, especially among those banks that are larger than $10 billion in assets and within the wheelhouse of their examination authority. There is a reason why that threshold was a big deal during the Dodd-Frank negotiations. I was flabbergasted, though, by the lengths they went to in order to satisfy their appetite for a trophy kill. Secret recordings of lower level management meetings and spies sent into branches in markets totally unrelated to where the original problems were found are just two examples of that. This was not a regulatory investigation; it was a James Bond novel. Apparently, the CFPB has inherited the playbook of the KGB.

Not only that, but in a settlement that was supposedly negotiated, they felt compelled to include in the complaint unnecessary and embarrassing quotes from their secret recordings just to rub salt in the wound. I can only hope that waterboarding was not used to convince the bank to accept the complaint’s content.

Make no mistake, the CFPB is on a war path, and it is scalps, not justice, that it is after. As an agency that is still trying to prove its worth and fend off political and judicial challenges to its constitutionality and unfettered administrative authority, the CFPB is more worried about justifying its existence than protecting its charge, the American consumer. What will happen to American consumers, though, much less our financial system, when the CFPB scares half of our community banks into ending consumer lending all together and assaults the reputation of the other half until their safety and soundness is compromised? They will be forced into the arms of industries much less regulated and unconcerned about their wellbeing, I’m sure. This case may be the best illustration yet of what happens when you separate the consumer regulator from the prudential one.

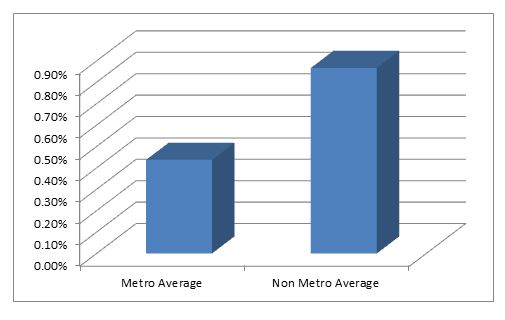

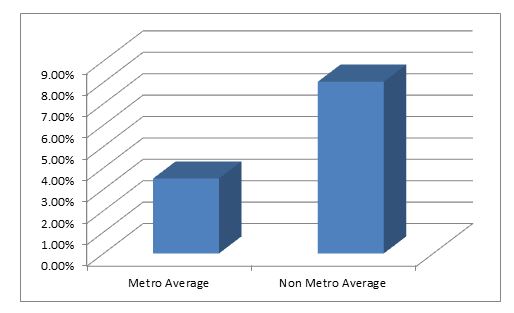

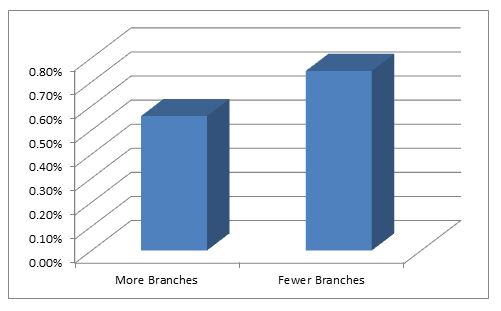

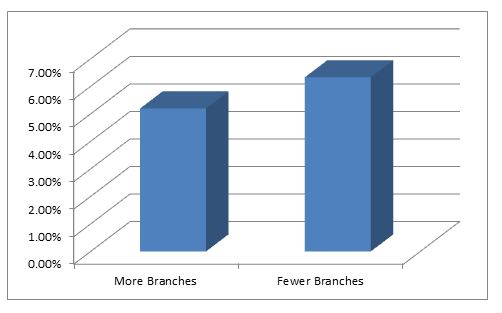

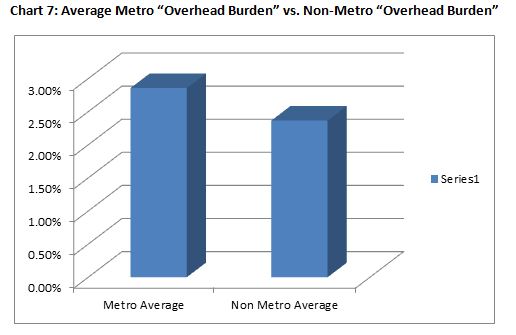

So why do metro banks spend more? Well, part of the reason may be tied to their large number of branch facilities which may be necessary to maintain market share in a larger market. According to that same data, banks in peer group categories with “more branches” had an average overhead burden to total assets of 2.79%, while banks in peer groups with fewer branches averaged a burden of 2.43%. Obviously, this would increase the costs related to occupancy and equipment, explaining why metro banks occupancy costs were higher than non-metro banks occupancy costs over that period (i.e., 0.44% average to total assets compared with 0.34% average to total assets) and banks with “more branches” carried higher occupancy costs as well (i.e., 0.45% compared to 0.33% for banks with “fewer branches”). Metro banks also averaged much higher “other expenses” (i.e., non-interest expenses excluding personnel and occupancy and equipment) than their non-metro counterparts (i.e., 1.28% on average to total assets relative to 0.97% for non-metro banks), and continuing with the theme that numbers of branches were the driver, banks with “more branches” averaged other expenses of 1.18% to total assets compared to an average of 1.07% for banks with “fewer branches.”

So why do metro banks spend more? Well, part of the reason may be tied to their large number of branch facilities which may be necessary to maintain market share in a larger market. According to that same data, banks in peer group categories with “more branches” had an average overhead burden to total assets of 2.79%, while banks in peer groups with fewer branches averaged a burden of 2.43%. Obviously, this would increase the costs related to occupancy and equipment, explaining why metro banks occupancy costs were higher than non-metro banks occupancy costs over that period (i.e., 0.44% average to total assets compared with 0.34% average to total assets) and banks with “more branches” carried higher occupancy costs as well (i.e., 0.45% compared to 0.33% for banks with “fewer branches”). Metro banks also averaged much higher “other expenses” (i.e., non-interest expenses excluding personnel and occupancy and equipment) than their non-metro counterparts (i.e., 1.28% on average to total assets relative to 0.97% for non-metro banks), and continuing with the theme that numbers of branches were the driver, banks with “more branches” averaged other expenses of 1.18% to total assets compared to an average of 1.07% for banks with “fewer branches.”